Inshore, Flats Fishing in Pineland

Fly Fishing Pineland

Deep Sea Fishing in Playa Herradura

Full Day Offshore

Salmon Fishing Trip

Steelhead Fishing Trip

Deep Sea, Nearshore Fishing in Puerto Aventuras

Fishing Charter, Puerto Aventuras

Deep Sea, Nearshore Fishing in Islamorada

4 Hour Half Day

Deep Sea, Nearshore Fishing in Islamorada

6 Hour 3/4 Day

Black Sea Trips

Deep Sea, Nearshore Fishing in Sarasota

Red Snapper December Re-Open

Winter Steelhead

We started Captain Experiences to make it easy to book fishing and hunting guides around the world. With over 2,000 Damn Good Guides, our platform makes finding and booking a trip seamless. Head here to check out our trips.

Flats Fishing

From Isolated atolls in the middle of the Pacific Ocean to Key West, all the way back around to Seychelles, Intertidal Flats ecosystems are some of the most beautiful and dynamic aquatic habitats on the planet. This holds especially true for the Florida Key’s seagrass flats that have such a special meaning to me. Aquatic plants help keep the water on the flats crystal clear while providing shelter for all kinds of marine life including snails, shrimp, crabs, turtles, stingrays, and manatees. A variety of fish species also call the flats home including my three favorite gamefish, Permit, Bonefish, and Tarpon. It’s no surprise that locations like this are sought after by so many outdoor enthusiasts and anglers.

Beyond the abundance of marine life they hold, there’s an undeniable attraction to these locations that motivates people to fly halfway around the world to visit. Unfortunately, overfishing and other human-caused disturbances threaten these fragile environments and the wildlife that resides here. Sadly, like many other aquatic habitats, there is not enough data or research to manage these areas correctly. To explore the basics of flats ecosystems, fly-fishing tactics, and some of the threats to these incredible natural beauties, let’s take a deep dive into the Florida Keys.

What are the Flats?

Flats are found in the vicinity of mainland or barrier island coastlines across the world. These aquatic environments are characterized by very shallow water and are highly sensitive to tides. Often during low tides, they drain entirely and be left fully exposed. Flats have low oxygen levels because the water is extremely shallow and is easily heated by the sun. This means that the organisms that live there must be able to tolerate the extreme environment. For this reason, most fish species only visit the flats to feed before retreating to deeper, more oxygen-rich, water.

The Bottom of the Food Chain

The Florida Keys are home to a variety of flats from seemingly barren intertidal flats, to lushly vegetated seagrass flats. Though, even the “seemingly barren” mudflats are teeming with life. The sediments on these tidal flats house a community of bacteria and algae which make the environment livable. More productive flats are covered in lush, green, grassy bottoms. The three types of seagrass: turtle grass, shoal grass, and manatee grass, are the foundation for a thriving ecosystem. They act as the maintenance crew for the flats with roots that hold the underlying sediments in place and prevent erosion. The grass also has spindly blades that catch sediment in the water column keeping the water clean and clear. Manatees also love to graze these grassy flats. So much so that they named a type of seagrass after them. Shrimp, starfish, and crabs feed on the grasses and are the main food source for the robust food chain in the flats. These food sources feed most of the fish, rays, and sharks that fill out the rest of the flat’s ecosystem.

A variety of birds are also dependent on the intertidal flats. When the tied goes out and the flat is exposed above the water, birds are free to roam in search of small organisms. Furthermore, the shallow nature of these flats is extremely crucial to small and juvenile fish because larger predatory fish are usually too big to swim on the shallow flats. Thus, the areas provide an oasis for them to survive, grow, and mature.

With bottom-dwelling organisms trying their best to find cover in the sandy sediment, the barren shallow water landscape turns into a voracious hunting ground. Fish with great eyesight like the Permit, move across the flats in groups of 3-4 and scour the sediment below looking for a meal. An unsuspecting crab trying to bask in the sun doesn’t stand a chance.

Predatory Fish on the Flats

The next step up the food chain on the flats is full of carnivorous fish species with some of the most popular including bonefish, tarpon, permit, redfish, snook, sea trout, and snapper. Although there is some overlap, each species prefers different types of flats or hunt in other areas on the flats.

Bonefish in the Shallows

Bonefish prefer sandy-bottomed sediments and super shallow water (I’ve caught some 9-pound bonefish in less than 6 inches of water). The shape and orientation of their mouth is also well suited for that type of environment. Their small mouths angle down toward the sediment so they can easily sift through the sediment looking for small organisms like shrimp or clams.

Bonefish are smaller fish (the world record is 15 pounds) which allows them to hunt in extremely shallow water where no other fish can compete with them. Because of the lack of competition, they can mill around on the shallow flats knowing larger predators, can’t reach them.

Given their small size, they are rarely seen by themselves usually traveling in packs of 3 to 100. Though they are ever-so-slightly easier to spot in such large groups, their silver coloration helps them disappear in crystal clear water with sandy bottoms. It is usually only when they churn up a cloud of dust after rustling around in the muddy sediment that you can spot them. Even then you are better off just casting into the murky cloud than trying to spot them. Bonefish are very skittish so waiting to cast until you get closer might not be an option. They live on the flats year-round and they notice if someone is intruding on their space.

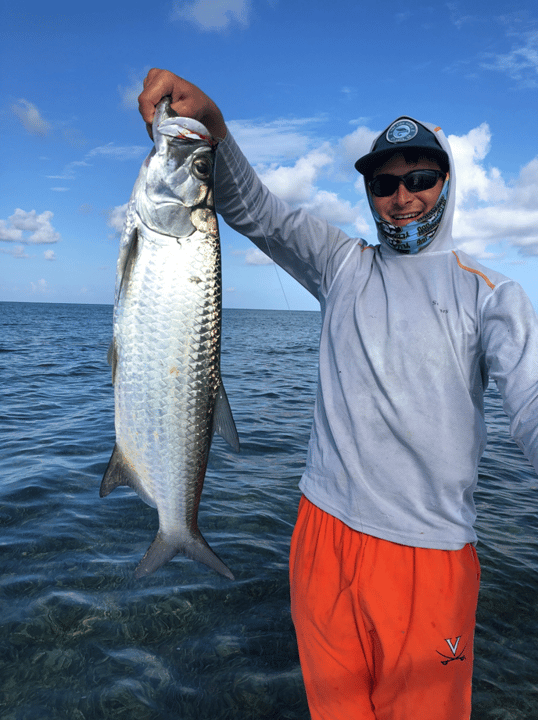

Tarpon on Patrol

Tarpon, on the other hand, are much larger and prefer deeper flats of 3-10 feet. Occasionally they can be seen crossing sandy flats, but they prefer to spend their time hanging out in grassy flats or mangroves. Tarpon prefer these conditions because they can grow to over 200 pounds and require more room to swim. Also called the “Silver King,” their dorsal fin is usually a darker shade of silver that blends in well with the vegetation. Most Tarpon don’t stay in the same place too long and are constantly on the move.

Unlike the Bonefish that live on the same flats for their entire life, Tarpon are known to cover a lot of water on long migrations of up to 1200 miles in a single season. Their usual migration pattern runs from the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico around the entire Gulf Coast and up the eastern coastline to Cape Hatteras. In extreme cases, tarpon have been found off the coast of the US with tags from South America that are believed to be several years old. It is also worth noting that some Tarpon don’t migrate. It is still not understood why some tarpon migrate and others don’t, especially given the wide range of data points. Some scientists believe they migrate to spawn in the deep ocean near the equator, some think they migrate to follow the water temperature, others think they may do it simply for fun.

The Elusive Permit

My personal favorite flats fish, the Permit, is the most elusive. They prefer to hunt sandy flats 3 to 5 feet deep but will spend most of the day in deeper water only coming to the flats to feed when the conditions are perfect. Even when they do venture up onto the flats, they are very wary of anything that is out of place.

Permit are medium-sized fish that can grow up to 60 pounds which allows them to dominate the 3 to 5-foot deep flats. They share the same silver coloration as bonefish and the tarpon, but because permit are a member of the jack family, they are not scaly. Permit closely resemble a large Pompano with a compressed body making it look tall and thin when viewed head-on. They are easily distinguished by their scythe-like fins and deeply forked tail.

Permit have the largest eyes in the jack family giving them exceptional eyesight and allowing them to spot prey at distance. They maneuver through the muddy flats deftly, usually in schools of 4 to 5, scanning the underwater savannah for crabs and shrimp. They are also commonly observed tailing large rays or sharks on the flats as they glide across the muddy flat looking for their own meal. When a shark or ray moves through the flats they kick up sediment holding food that permit prey on. This allows permit to hang back and wait for a disoriented shrimp or crab to pop out and snatch it out of the water.

Beyond their sharp wits, permit are elusive in large part due to their eyes. Their eyes let them spot every threat or anything out of place. This makes it extremely difficult to catch one on a flyrod because fly fishing requires artificial lures (often made of feathers no less). While a Tarpon or a Bonefish will usually eat a feathery blur that resembles their favorite snack dancing around them, permit can almost always tell the difference. For this reason, permit have become the ultimate test for fly fishermen. In order to catch one on the fly, you have to make a perfect cast at a fast-moving and small target that’s usually more than 25 ft away while the wind whips you around. Even if executed perfectly and the fly lands on their nose, you still need a certain amount of luck for a permit to bite.

Cuba Flats Fishing Trip

A similar event happened to me last summer when my father took my brother and me on a “fishing trip” to Cuba in June. I use quotations there as we obtained our travel visa under the guise of “Scientific Research”. We were excited because Cuba is considered a prime saltwater fishing location due to its expansive network of archipelagos, coral reefs, and pristine flats that rarely get any fishing pressure. We spent the first half of the week catching all the tarpon and bonefish that we could handle. We caught all of our fish on the fly too because it is the only fishing method they allow in Cuba.

With our success early on we decided to try our luck targeting permit. The guides were phenomenal as they push-poled us around the flats on a skiff, while we had multiple good opportunities to catch a permit. My first couple of attempts weren’t perfect enough by any means, but I was slowly improving.

Finally, I put the perfect cast on a big Permit using a shrimp imitation fly. It fell right in front of his nose and I watched as he made a move for the fly. As I stripped the line and watched him go for the bait. I felt a tug on the end of my line. I was certain I was hooked up with my first ever Permit on the fly when the tug started to feel very light, and jerky. This is not normal for a mature Permit that usually runs and fights like crazy. I quickly reeled in the line to find a small Mangrove Snapper attached to the end of my hook. I was devastated. I finally got a Permit to go for my fly and this stupid little mangrove snapper had stolen it right out of his mouth, just my luck.

I relayed my tragic tale to the rest of the guys that night, thinking it was a fluke of misfortune, but everyone confirmed the same thing had happened to them. Everyone seemed to have permit make a move on their fly only to have it immediately stolen away at the critical moment by a dinky fish. We curiously debated why this was happening, and why the snapper didn’t eat the fly before the Permit made its move.

The oldest guy in our party, clearly a veteran fly fisherman, eventually spoke up and explained what was going on. He told us that the fish on the flats know permit have the best eyesight. Smaller fish like snapper, are immediately attracted to the fly when it hits the water, but if a Permit is around it will wait and see if it decides that it’s okay to eat. As soon as the permit makes a move to eat the fly, the snapper decides “well if the Permit thinks it’s okay, I better eat it” and will dart up and steal it from him.

This happened to me four more times over the remainder of my stay. Four big Permit, four perfect casts, and four times my shot at a permit was stolen by a snapper. I was forced to leave empty-handed and the images of those permit moving in on my fly still haunt me today. Pesky snapper!

What’s Happening in the Keys?

In contrast to Cuba’s absence of fishing pressure, the keys are not only a popular place for anglers, but it’s also crowded with tourists. The increasing recreational and commercial presence in the Keys has had some significant adverse effects on this fish as well as the flat’s habitats in which they live. Beach-colored stipes rip across the once pristine seagrass flats all over the keys. Though all the flats in the Keys have been deemed “National Marine Sanctuaries” since 1990, visitors who don’t know the rules often tear across the flats in their boats or jet skis demolishing flats habitats that take decades to regrow. Yes, they will get fined, but the damage has already been done. The accidents add up, and the Florida Key’s flats continue to be damaged.

Another immediate concern in the area is that the native bonefish, which was once the staple of the Florida Keys, has completely vanished in the past 10 years. At one time they were so abundant you couldn’t keep them off your line but since 1990 the bonefish population has fallen off dramatically in the Keys. Concerned scientists and anglers have many different theories to explain what happened to the bonefish from commercial shrimping that depleted their food supply, to increased boating pressure near the flats. Unfortunately, there just isn’t enough evidence, data, or previous research on the topic to create change.

Fortunately, organizations like the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust are trying to get to the bottom of the issue. They are trying to make a difference in the keys and all over the world by asking both public and private sectors, what information they need to make changes that will help the flats make a comeback. After identifying information that needs to be collected, they try to find, and fund, groups that will go out and collect it. Their most recent and successful accomplishment has been putting an economic valuation on the annual revenue generated from the Florida Key’s flats ecosystem. This allowed legislators to at least look at a numerical representation of the area. Sadly, it’s difficult to put a number value on a shared natural experience like the flats in the Keys. More research and data are the only way to help the Florida Keys return to its former glory. With growing groups of conservationists continuing to support research, improvement will certainly come.

Joey Butrus

Updated on August 3, 2023

January 7, 2022

June 28, 2023

November 15, 2023

June 3, 2021

October 26, 2020

Related Articles

May 5, 2021

November 29, 2021

July 14, 2023

Featured Locations

- Fishing Charters Near Me

- Austin Fishing Guides

- Biloxi Fishing Charters

- Bradenton Fishing Charters

- Cabo San Lucas Fishing Charters

- Cancun Fishing Charters

- Cape Coral Fishing Charters

- Charleston Fishing Charters

- Clearwater Fishing Charters

- Corpus Christi Fishing Charters

- Crystal River Fishing Charters

- Dauphin Island Fishing Charters

- Daytona Beach Fishing Charters

- Destin Fishing Charters

- Fort Lauderdale Fishing Charters

- Fort Myers Fishing Charters

- Fort Walton Beach Fishing Charters

- Galveston Fishing Charters

- Gulf Shores Fishing Charters

- Hatteras Fishing Charters

- Hilton Head Fishing Charters

- Islamorada Fishing Charters

- Jacksonville Fishing Charters

- Jupiter Fishing Charters

- Key Largo Fishing Charters

- Key West Fishing Charters

- Kona Fishing Charters

- Lakeside Marblehead Fishing Charters

- Marathon Fishing Charters

- Marco Island Fishing Charters

- Miami Fishing Charters

- Montauk Fishing Charters

- Morehead City Fishing Charters

- Naples Fishing Charters

- New Orleans Fishing Charters

- New Smyrna Beach Fishing Charters

- Ocean City Fishing Charters

- Orange Beach Fishing Charters

- Panama City Beach Fishing Charters

- Pensacola Fishing Charters

- Pompano Beach Fishing Charters

- Port Aransas Fishing Charters

- Port Orange Fishing Charters

- Rockport Fishing Charters

- San Diego Fishing Charters

- San Juan Fishing Charters

- Sarasota Fishing Charters

- South Padre Island Fishing Charters

- St. Augustine Fishing Charters

- St. Petersburg Fishing Charters

- Tampa Fishing Charters

- Tarpon Springs Fishing Charters

- Venice Fishing Charters

- Virginia Beach Fishing Charters

- West Palm Beach Fishing Charters

- Wilmington Fishing Charters

- Wrightsville Beach Fishing Charters